A Chat with Amby Burfoot

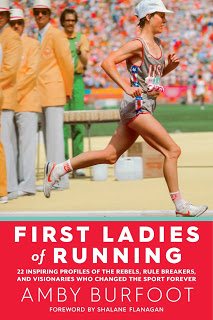

Amby Burfoot’s name is synonymous with the sport of running. He has served as an editor and writer at Runner’s World since 1978. He is a member of the Running Hall of Fame and the winner of the 1968 Boston Marathon. Over the course of his career, he has run over 100,000 miles, including a personal best 2:14:29 marathon. His latest book, First Ladies of Running, released in April, chronicles the stories of twenty-two pioneering women who broke gender barriers and paved the way for today’s female runners. Recently, I called him at his home in Mystic, CT, to chat about his new book and all things running.

Amby Burfoot’s name is synonymous with the sport of running. He has served as an editor and writer at Runner’s World since 1978. He is a member of the Running Hall of Fame and the winner of the 1968 Boston Marathon. Over the course of his career, he has run over 100,000 miles, including a personal best 2:14:29 marathon. His latest book, First Ladies of Running, released in April, chronicles the stories of twenty-two pioneering women who broke gender barriers and paved the way for today’s female runners. Recently, I called him at his home in Mystic, CT, to chat about his new book and all things running.

A: When did you decide to tackle the topic of female pioneer runners and why?

Amby: I came up with the idea about four years ago. I love the history of running, and I love the recent history of women’s running. And I had this blank question, “Gee, I wonder if anybody has ever pulled together a couple dozen of the great women’s running stories and put them in one book?” And I was kind of surprised to find that no one had. I have a number of women’s running books on my bookshelves, but they are either individual biographies or a range of other stories. So, one, no one had done it yet. And, two, I grew up in that era. My competitive days were the 1960s and 1970s, so I knew many—if not most—of the women on a personal basis. Not only did that make it more interesting to reconnect with them, but it made it a little bit easier because they knew who I was—and I think they had a decent opinion of me. [laughing]

A: Along that note, many of these women—Julia Chase in the 1961 Manchester Road Race and Bobbi Gibb in Boston in 1966, for example—were running at the time your own career began to rise. When you saw these women at races or perhaps read newspaper headlines, did you sense the significance of what was happening at the time? Or was it a more subtle realization?

Amby: It was more subtle. One of the things that I noted in the New York Times essay—and perhaps not in the book—is that it wasn’t as if one or two women entered a race, and suddenly the floodgates were open, and the next year there were a thousand women at Boston, for example. It was very, very slow at the beginning. They were so far ahead of their time, there really weren’t many women chomping at the bit to get into road running, so there wasn’t a great release when one or two did. But that has a way of making them sound less important or less epochal, so I always add that it makes their actions more courageous and more forward thinking. It gives us a sense of how rare and unique they were.

A: You could argue that compared to major sports like football or baseball, running is on the fringe of sports coverage. How widespread was the coverage, really, when Bobbi Gibb ran Boston? You mention in your book that Joan Benoit hadn’t even heard of Bobbi when she ran Boston in 1979.

Amby: Joan was quite a ways later, and the only way you would have heard about Bobbi would have been if you were reading the newspapers in ‘66, ‘67, and ’68—pretty much only in Boston. There were four or five newspapers, then and they all covered the marathon, and they covered Bobbi particularly the first year. But Joan was almost fifteen years later and not reading newspapers [when Bobbi ran]. It took the gradual, one by one, brave individual to get things going. Then, as the times changed, the continual flow of women into the sport proved to the world that women really were outstanding endurance runners and, moreover, could complete twenty-six miles without any physiological harm whatsoever, despite all the crazy stories that circulated in the early days.

A: The rise of women’s running was a grassroots movement, as you show in your book—very small, little pockets of movement. You said that while you hate to try to give a sweeping quality to all the pioneer female runners, if you were forced to, one of those qualities would be that they were driven by a pure love for the sport. It wasn’t like there was someone on a national stage they were looking up to. It was just them, as individuals, making these courageous decisions to run.

Amby: Yeah, we didn’t begin to have a national movement until Title IX, and I always refer to the Bobby Riggs-Billy Jean King match, which I think was in ’73. Those things really put the gender question in sports on the front burner. But before then, it wasn’t a movement. It was just lone individuals propelled by their own love of sport, and particularly those who found themselves attracted to the freedom and easy movement and nature-base of running. It was the love of that, and of course, once you love something, it’s only human, especially in a competitive society, to want to see what you can do, where you stand, how you match up. These women weren’t thinking about the Olympics. They weren’t thinking about breaking three hours or anything. They wanted to be on the starting line and see what they could do. And that was a struggle in the early days.

A: I think one of the most surprising chapters in your book is the last one, in which you talk about running the final twenty-three miles of the Marine Corps Marathon with Oprah. Your respect for her, and your admiration for what she did in that race, is evident. It was very eye-opening.

Amby: As soon as I realized she was in Washington, D.C., to run the marathon—and I was in Washington, D.C., hanging out and promoting Runner’s World—I immediately thought, “Well, this is the most famous person who has ever attempted a marathon, and I’m the editor of Runner’s World. Geez, I’d better get in there and run it with her.” So that’s why I went down to the Pentagon parking lot and waited for her, not knowing that the National Enquirer had two runners assigned to run on each side of her and a half-dozen photographers on motorcycles. I’m sure they were hoping for a hugely embarrassing event to record, but she just ground it out. It was very, very impressive. To this day, I think people can tell when they hear me talk about it that I was authentically impressed by her dogged effort. I mean, on that day, she had all of the qualities that all of us hope to have when we’re running our best marathons.

A: Did you know she would be accessible in that race or that you would be able to at least run near her?

Amby: I didn’t know if she would be accessible or not. The two National Enquirer guys ran on each side of her. I think their bosses most have told them to do that. I kept what I felt was a respectable distance and ran maybe 10 or 20 yards behind her, which was also a good place to watch the entire effort, particularly the incessant number of other runners coming up beside her. They would clap her on the back and shoulder, wish her well, say you’re an inspiration and we’re so glad you’re out here. In the early miles, she tried to acknowledge them all. Then as she got tired much later, she couldn’t do it anymore, of course. She just kept her head bowed forward and kept chugging along.

A: It’s almost staggering to have that visual in my mind and know that that was just ten years after Joan Benoit’s historic Olympic victory.

Amby: Yes, and furthermore, although no one can ever prove cause-and-effect, the real women’s running boom came after Oprah, not after Joan. That was really called out for me, recently, when I looked at some Boston Marathon statistics for the Bobbi Gibb article. I saw that there was a steady rise in women’s participation all the way through the early ‘90s, and then in the late ‘90s, participation just took off in leaps and bounds. So, I think by and large, most of today’s women’s runners—not to mention the men’s runners, as well—know that they’re not going to win the Olympics, know they’re not going to win the Boston Marathon or set a record, and are more inspired by examples of achievement by people who don’t look like Olympians than they are by the super performances of the obvious Olympians. So an Oprah—or any number of other people who have had to deal with things in their lives and have proved that they can still go the distance—those are the stories that are inspiring to everybody.

A: During the process of writing First Ladies of Running, was there a story or experience that struck you as completely unexpected?

Amby: Well, those were endless. But my favorite story or anecdote goes to the only woman I have not personally met at this point. And she is the first woman [in the book], Grace Butcher. She attended her first track practice in 1949, which is a decade before anyone else in the book. So, a month ago, I’m sitting in the theater watching the Jesse Owens movie that came out recently, Race. It recounts the year 1934, when he sets four world records, and it shows him setting the four world records. In one scene, he gets down for the start of the race—and it’s a cinder track—so of course he has a garden trowel, and he’s digging his starting hole. And I’m watching him dig his hole, and he’s scooping up the cinders in the direction of the line that he’s going to run. And right away, I said, “No! That’s not right!” Grace Butcher told me that in her first track practice in 1949 the only thing they were taught was how to dig holes for starting. You dig your hole perpendicular to the direction you’re going to run. That way you get a really steep and firm back side of the hole to blast off of. So from Grace Butcher’s story, I learned one of the little faults of the Jesse Owen’s movie. [laughing] Never in my life has someone educated me on how to dig a starting hole with a garden trowel. But that was lesson one on day one if you went to track practice in the 1940s.

A: Did you purposely time the release of your book with the 50th anniversary of Bobbi Gibb’s historic Boston Marathon or was that a nice coincidence?

Amby: I absolutely did that. I saw that coming a number of years out. And I knew that 2016 was an Olympic year, so the top Americans would not be running Boston. There wouldn’t be as many stories about Shalane Flanagan and Meb Keflezighi, so that would mean Bobbi would get even more publicity. She would fill the void. All of that worked out very nicely. [laughing] But better than the skullduggery and marketing that we’re talking about, we had wonderful reunions and seminars in Boston with Bobbi. One afternoon, we spent an hour and a half with her. The next day, about six or seven of the additional first ladies who have run Boston were also at a seminar. There was just a wonderful warm feeling that everybody was there to support Bobbi and women’s running. And everyone was also having a great time at what ending up being a kind of pajama party—many of them stayed together in one home in Cambridge.

A: That’s one thing that makes your book so special: your firsthand experience. I don’t think there are many people who could write a book like this and be able to say about each chapter, “I knew this person or I watched this person race.” In your experience covering the sport for Runner’s World, is there a moment that stands out to you? A go-to party story where you lean back and say, “I remember the time…”

Amby: That’s something I’d have to think about. Certainly, with particular reference to the culmination of the First Ladies book, I was fortunate enough to be in the Olympic stadium when Joan Benoit came running in in 1984. And, honestly, we’re all supposed to be objective, hard-core journalists, but everybody in the row with me—we all had tears in our eyes. We were all track journalists, male and femal both, and we had all seen the fight to get the women’s marathon into the Olympics. We’d seen the gestation of ten years and more. To finally have the moment arrive, and finally to have everybody’s favorite pioneer pilgrim from backwoods Maine come in such a spectacular winner—I don’t see how you could not have damp eyes at that moment.

A: If people buy the book through your website, they can get an autographed copy, right?

Amby: That’s right. And my outlandish dream is that parents around the country will buy the book for their daughters and nieces and their friends who are running junior high and high school cross country. Because that’s where there is so much excitement around young girls running right now.

Amy L. Marxkors is the author of The Lola Papers: Marathons, Misadventures, and How I Became a Serious Runner and Powered By Hope: The Teri Griege Story. Click here to receive Amy's weekly article via email.

Connect With Us

see the latest from Fleet Feet St. Louis