Why You Don?t Need to Train Faster to Run Faster

Sensational headline, I know. It likely belongs on the cover of a magazine being sold at the checkout line at a grocery store, but bear with me because it’s actually quite true.

You see, one of the most difficult concepts to master as a runner is that you don’t need to be running faster, longer or harder every time out to improve. In fact, sometimes running just below or slower than your potential in workouts leads to more consistent improvement.

This flies in the face of almost every other sport we’ve been exposed to.

Lift weights?

Then you know a good goal is to add weight to the bar every week.

Play basketball?

You darn well better make more free throws then you did last month.

But, this isn’t the case with running. More importantly, the mindset of always needing to train faster in order to race faster is what leads to overtraining and injuries.

Why is this? What makes running so different from other sports that it completely changes the way we need to think about training?

That’s what we’re going to explore in this article. And, although the title may lend itself to a trashy magazine, the research and science we use to help you understand this concept will make this one of the most informative articles you’ve read in a long time.

How You Become a Better Runner

At the most basic level, your performance while running is determined by how efficiently you can utilize oxygen to aid in the breaking down of fuel and then transporting that fuel and oxygen to your running muscles. This is often referred to as the aerobic system.

Of course, that’s simplistic as there lots of other factors that contribute to running performance.

However, almost all of these other performance indicators link back to the aerobic system in some fashion and it’s the most essential component.

Now, what makes running different from most other sports is the amount of time it takes to improve this process.

For example, mitochondria play an essential role in how efficiently you can utilize oxygen. Mitochondria are microscopic organelle found in your muscles cells that contribute to the production of ATP (energy). The more mitochondria you have, and the greater their density, the more energy you can generate during exercise, which will enable you to run faster and longer.

The problem with developing mitochondria is that it happens very slowly. Moreover, mitochondria have a half life of one week. Simply speaking, you’re able to gain half of the potential benefits to your mitochondria each week that you train.

For example, if you went from no training to running 25 miles, you’ll realize 50% of the benefits of that 25 mile week. Run 25 miles the next week at the same intensity and you’ll realize 25% of the benefits from week one. This continues until you reach 100%.

Here’s a simple chart to explain it:

| Week 1 | 50% of benefits of 25mpw | up 50% |

| Week 2 | 75% of benefits of 25mpw | up 25% |

| Week 3 | 87.50% of benefits of 25mpw | up 12.5% |

| Week 4 | 93.75% of benefits of 25mpw | up 6.25% |

| Week 5 | 96.88% of benefits of 25mpw | up 3.125% |

| Week 6 | 98.44% of benefits of 25mpw | up 1.5625% |

This is a simplistic progression since it assumes you do not increase you mileage or intensity over this six week period.

However, it does demonstrate how you benefit from mitochondria development and how it is critical to slowly increase training stimulus and training volume with time.

That’s a long time to fully benefit from the training you’re putting in.

Let’s compare that to strength training or even playing basketball. These sports rely on fast twitch muscle development and neurological pathways to improve.

The nervous system responds quickly to new stimuli because the growth and recovery cycle is very short. In fact, you can make small improvements to your neuromuscular coordination in less than a day. The same can be said for fast twitch muscle development.

As such, it’s much more common to see gains in strength or ability on a consistent basis over a short time period, like a week.

Continuum of Thresholds

Ok, so now you understand the physiological factors that lead to improved running performance and how long it takes to develop them. But, we still haven’t answered the question about why running at your upper limits or faster each week doesn’t work.

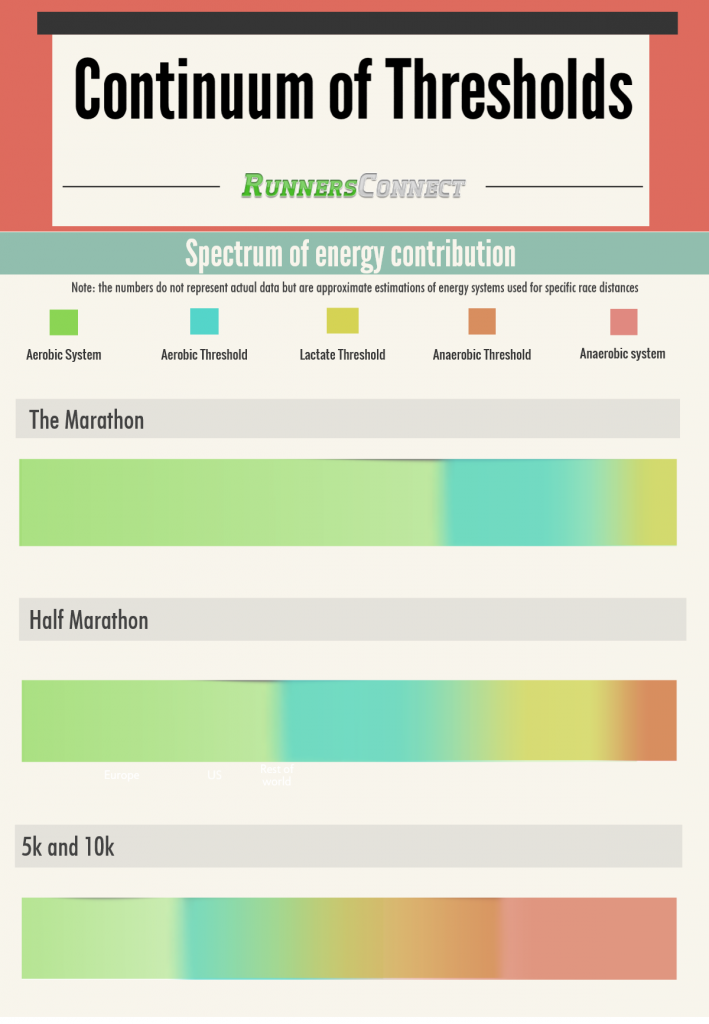

To explain this concept, I think it’s best if we start with looking at this graph which shows the spectrum of energy contribution required to perform well at commonly run race distances.

The first thing to point out with this graph is that energy systems in running aren’t independent. You can still be using the aerobic pathway while running at your lactate threshold.

Furthermore, although we talk about energy systems like lactate threshold, anaerobic threshold, etc as if they have finite starting and ending limits, you can see that they can actually be a little fuzzy.

Now:

What does this chart mean for your training?

In all events, you’ll find a much greater dependency on energy systems in the “slower” range rather than those in the faster range.

Take for example the half marathon. While the race relies more heavily on the lactate threshold zone, a large proportion of energy still comes from the aerobic system while very little is needed from the anaerobic threshold.

That means the predominance of your training needs to occur in these heavily used systems which are best targeted at slower paces.

If you err and run faster then your physiological target, whether it be because you felt good or because you were being aggressive, the value you gain from the workout drops significantly.

Here’s the deal:

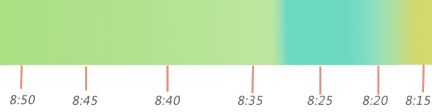

Let’s assume you’re a 3:50 marathon runner looking to target your lactate threshold. On the continuum, your paces might look something like this…

If you’re training on the conservative side or maybe even training for something like a 3:55, just to be safe, your target for the lactate threshold run might be 8:25 to 8:35 pace.

Even though 8:35 might miss the bulk of the lactate threshold zone, you still put in training at your aerobic threshold, which still helps for race day.

On the flip side, if you get aggressive with your workouts and decide to push the limit of your training, you might end up running 8:15. Now you put yourself in the anaerobic threshold zone, which isn’t needed for the marathon. Even though you ran faster than you’re 8:35 counterpart, you got less value and fitness from the workout.

This situation of running faster but getting less benefit most often happens when workout conditions are not ideal (like it’s hot) or you’re not “firing on all cylinders”.

When this happens and you’re operating at say, 95% of your normal, that 8:25 pace now has the corresponding effort of an 8:15 pace. Thus, you likely worked a bit more of the anaerobic threshold then you intended.

How many times have you stubbornly gone out and tried to hit your paces, despite them feeling much harder than you think they should?

I know I do it all the time.

Now:

If you’d erred on the side of caution and did not pushed the limit of your training paces, you would have stayed in the lactate threshold zone and, at worst, built up your aerobic threshold more.

Research Shows Moderate Workouts Beat Hard Workouts

Of course, me explaining these concepts anecdotally is nice, but if you’re a RunnersConnect fan, then it’s because you want more concrete data to back up your training decisions.

That’s why in an earlier post I documented a really cool research study that demonstrated how after 12-weeks of training, two groups of athletes – one who trained at high intensity and another group who trained at moderate intensity – both achieved the same level of improvement to VO2max.

I won’t document my full analysis, but the conclusion I believe the data shows is that moderate, consistent workouts beat hard, gut-busting workouts during the entire length of your training cycle.

How to Apply to Your Training

Now that you understand how this works, how do you apply these concepts to your training?

Of course I’m not suggesting you never push yourself in training.

Far from it.

I’m merely prompting you to ask the question to yourself – “is pushing my pace today or trying to make a big leap this training segment the right decision for my training long-term?”

Let me give you three tips.

When given the option, choose to go 90% rather than 100%.

My good friend Blake Boldon once said, “It’s better to be 90% prepared and 100% healthy than 100% prepared and 90% healthy.” I couldn’t agree more.

You can still race well and PR if you’re only 90% fit, but I’ve rarely seen a runner go into a race injured and walk away with a great performance.

What usually happens is that injured runner hurts him or herself even more during the race and then is forced to take time off and sets themselves back for their next race. Whereas the 90% fit runner has a good, sometimes great performance, and then is able to carry that fitness right over into their next training cycle.

Don’t feel the pressing need to up your paces every week or every month

This is the most common mistake I see and actually the reason I wrote this article. Here’s what usually happens…

Athlete: “Coach, I’ve been running great these last 6 weeks. I’ve hit all my workouts and felt good. Shouldn’t I start increasing my training paces?”

Me: “Looks like you’re still hitting the right training zones. Let’s stick with these paces as they are clearly working.”

Athlete: “Then how am I supposed to race faster? I can’t improve if I don’t train faster, right?”

I totally understand this line of thinking and it’s exactly why I wrote this article. If you’ve ever thought this or asked this to your coach, re-read this article to better understand why.

Workouts are not designed to prove fitness

Another wise coach, Scott Simmons, once told me: “Workouts are for improving specific physiological systems, not for proving how fit you are. You prove your fitness on race day.”

Use this new-found knowledge to your advantage this training cycle and see the gains you can make with consistent, moderate workouts!

Written by Jeff Gaudette

Connect With Us

see the latest from Fleet Feet Mobile